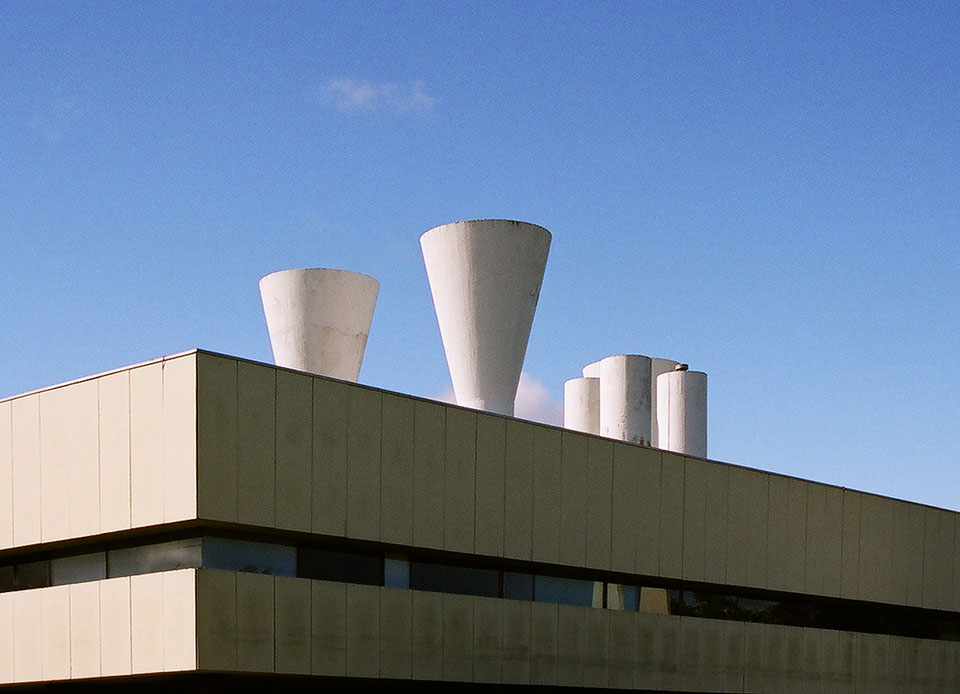

British Gas Engineering Research Station

1967

My favourite anecdote concerning the British Gas Engineering Research Station comes from Peter Yates, quoted in the Architects’ Journal. The firm instructed the contractor to make the 18 ton venturi trumpets better than anything he had done prior. ‘It will come from the shuttering both straight and exact. For the aggregate, man-made silica very hard and white; fine white Portland cement, the first batch to be produced; and to mix concrete, instead of water, you will use milk.’ According to Yates, they did! [1] Ryder and Yates were out on a limb, geographically and stylistically. I have often held that the north-east is something of an island, unlike the rest of the north, which is tightly strung together from Liverpool to Hull, the Tyne-Tees conurbation is detached and distinct. Culturally, it might be argued that with talent and commitment one could steer a creative course with unique qualities and I would say this applies to Ryder and Yates. Their buildings were not like other post-war modernists and clearly drew on their experience with Lubetkin and le Corbusier, but also maintained a language of their own. Simplicity and the refining of elements characterised their approach and minimalism met with mythology to create a commercial architecture that spoke to architects. This building never quite had a brief, the type and amount of research that would take place there was constantly changing during the design and construction phases and continued to change once it was complete.[2] Ryder and Yates designed flexibility into the scheme perhaps acknowledging their lessons from Lubetkin, ‘that nothing is fixed’. [3] The building had to account for rapid expansion and for the laboratories to be turned to any experiment that was required – gas had just been discovered in the North Sea. With few UK precedents to turn to, Ryder and yates drew inspiration form Eero Saarinen’s Bell Research Centre. The open-ended research space was anchored by a fixed component for parking and administration ‘all zipped up in a rectangular packet of painted precast concrete facing slabs and strip windows.’ [4] Beyond this reductive approach, like many of their schemes, the building was afforded character by formal flourishes that were inexpensive, but sculpturally expressive. Here, the trumpets were accompanied by an over-accentuated portal and two earth mounds that leant a certain ambiguity to the transition from ground to building. Nearby were the firm’s administrative headquarters for Norgas and their own office (both on this website). The project architect was G W D Harris.

[1] Architect’s Journal, 12 November 1975, p.993

[2] Architects’ Journal, 24 February 1982, p.49

[3] Architect’s Journal, 12 November 1975, p.993

[4] Architect’s Journal, 24 April 1968, p.894