Civic Centre

1967

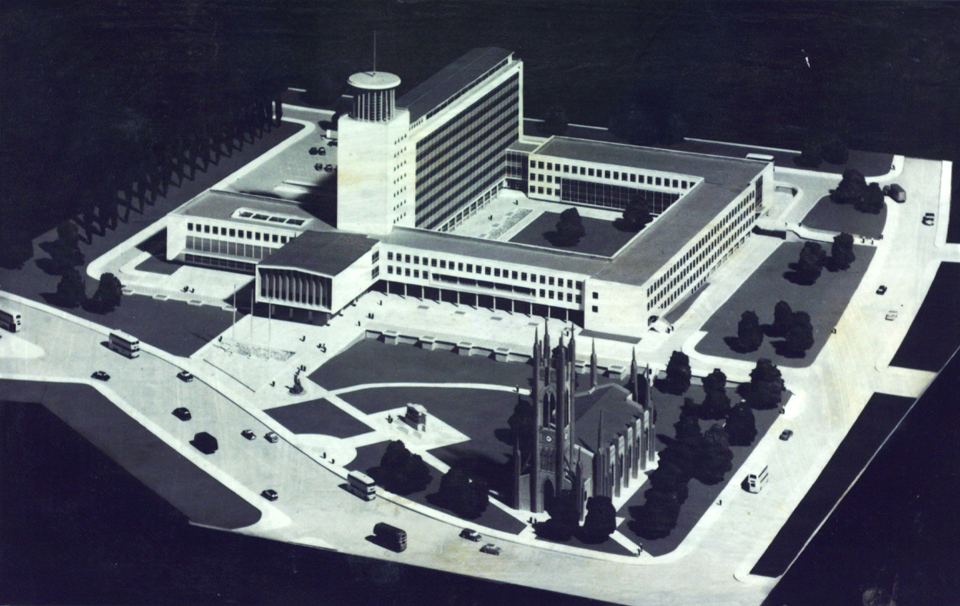

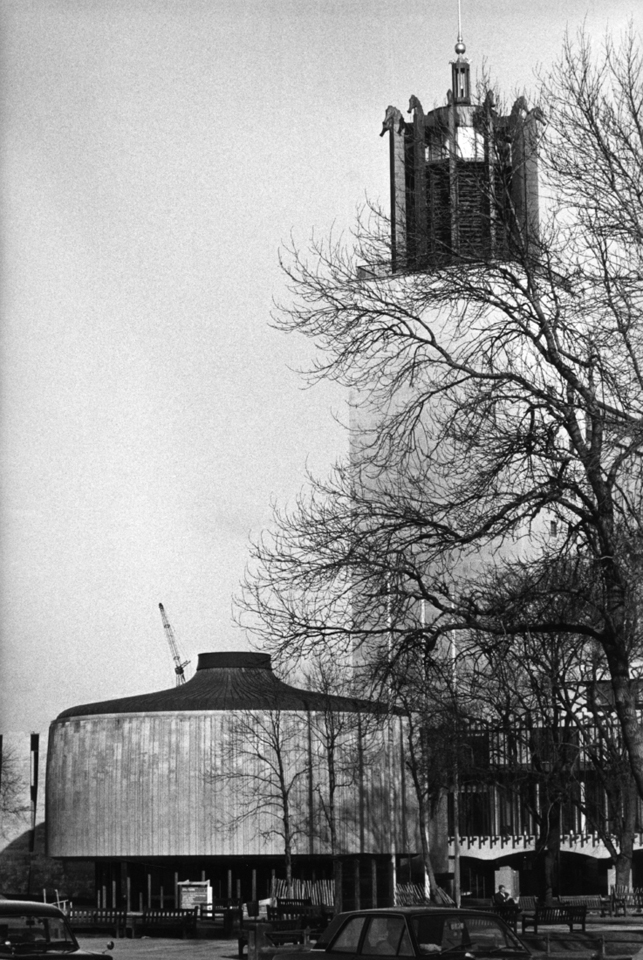

Without wishing to be accused of having a chip on my shoulder, it is telling that this building, now lauded as one of the finest examples of civic architecture in the country, was only published in the periodicals Building and Architect & Surveyor when it was completed. Nowhere in the pages of the Architectural Review and two appearances in the Architects’ Journal – one photograph of a model in an advert taken out by the City Architect’s Department about their restructuring and a second news item announcing the appointment of London based Design Research Unit (DRU) to produce the wayfinding for the scheme. How this should be interpreted is open to speculation, but as someone who champions architecture of the state and of the regions, to me this omission is symptomatic of a prevailing architectural culture that has always focussed on the south-east of England. It may, however, also be accounted for in the genesis of the scheme, a ‘Town Hall’ originally won in competition in 1939 by Collins and Geens, reported in the AJ and unbuilt due to the outbreak of war. The built scheme, designed by City Architect Georg Kenyon from 1950, began its construction in 1958 and, as Susan O’Connor identified, adopted the nomenclature and form typical of many such ‘civic centres’ of the post-war period – an administrative block or tower and a pronounced council chamber. [1] In the case of Newcastle, the council chamber was round in plan and a prominent public facing feature of the scheme, set back from the surrounding streets to enhance the ceremonial sense of approaching the building. Arranged on two perpendicular axes, the southerly approach is along a richly colonnaded undercroft lined with nine flambeaux and ornate modernist metal screens by Charles Sansbury. This vista is terminated with a powerful statue of the River God Tyne by David Wynne that pronounces the space between administration and democratic decision making and is animated by the way that rain soaks the surrounding stone façade, dripping and draining from Tyne’s body as if he has just emerged from the River. The interior is richly decorated, both in its finishes and its artworks, including a mural by Victor Pasmore and a hung tapestry by John Piper. Such quality was celebrated by the brash council leader of the 1960s, Dan T. Smith, a controversial figure eventually embroiled and disgraced in a well reported corruption scandal. It also led to the listing of the scheme at Grade II* in 1995.

[1] O’Connor, S. (2017) ‘The Body Politic and the Body Corporate: Symbolism in the 1960s’ town halls and its precedents’, Twentieth Century Architecture, no. 13, pp.163-176.