Tinbergen Building

1970

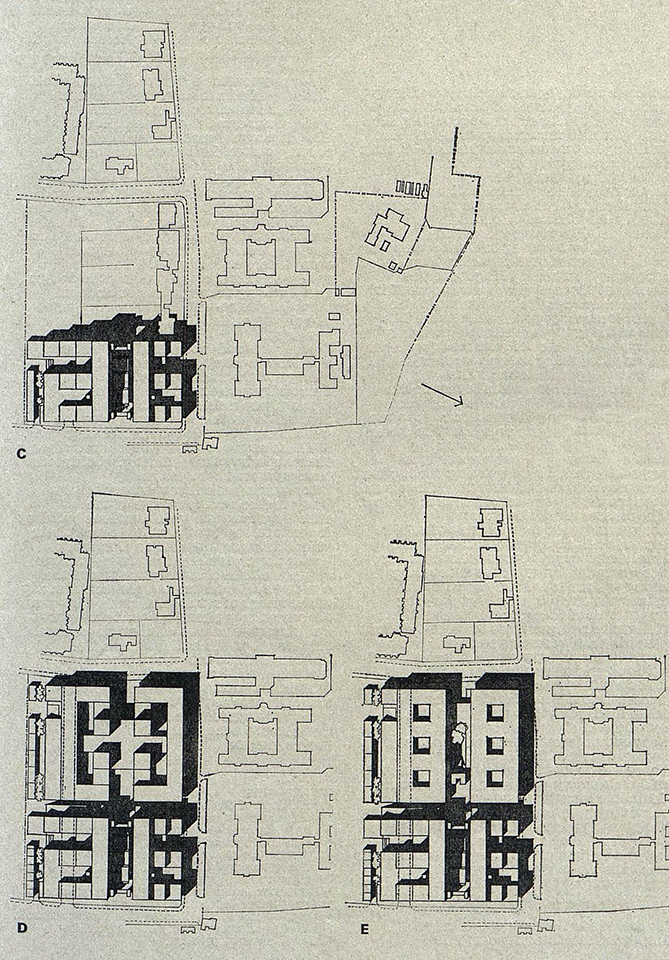

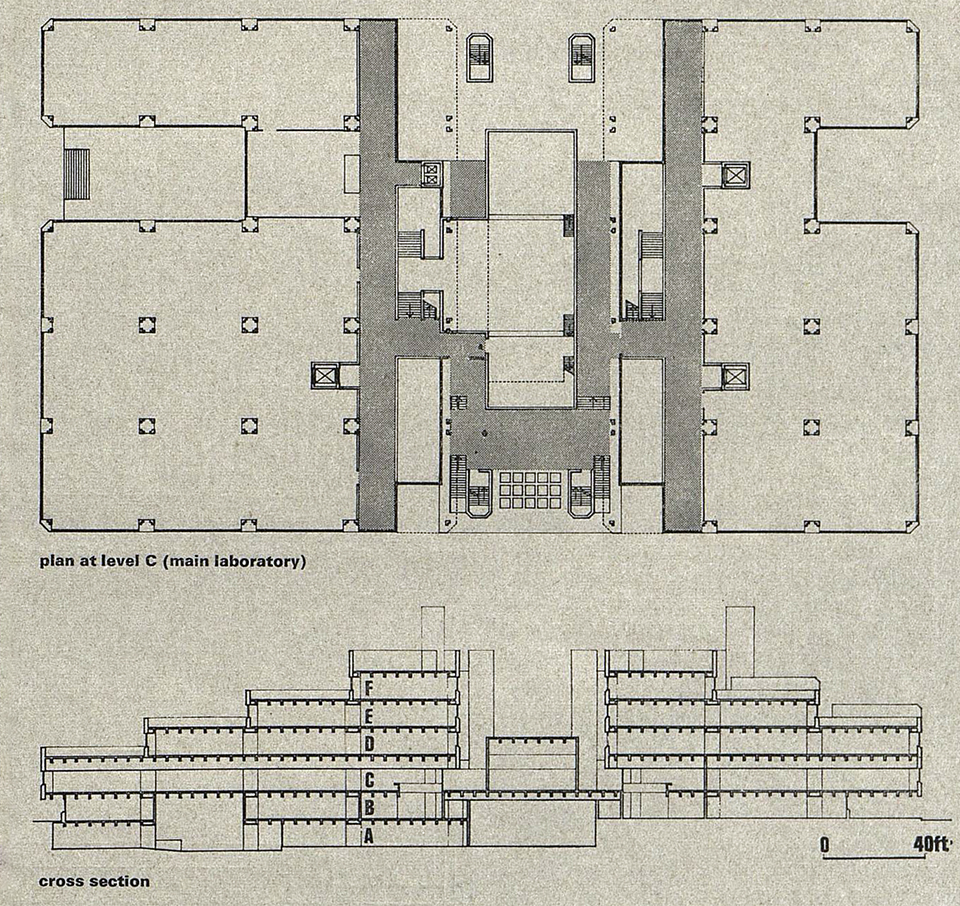

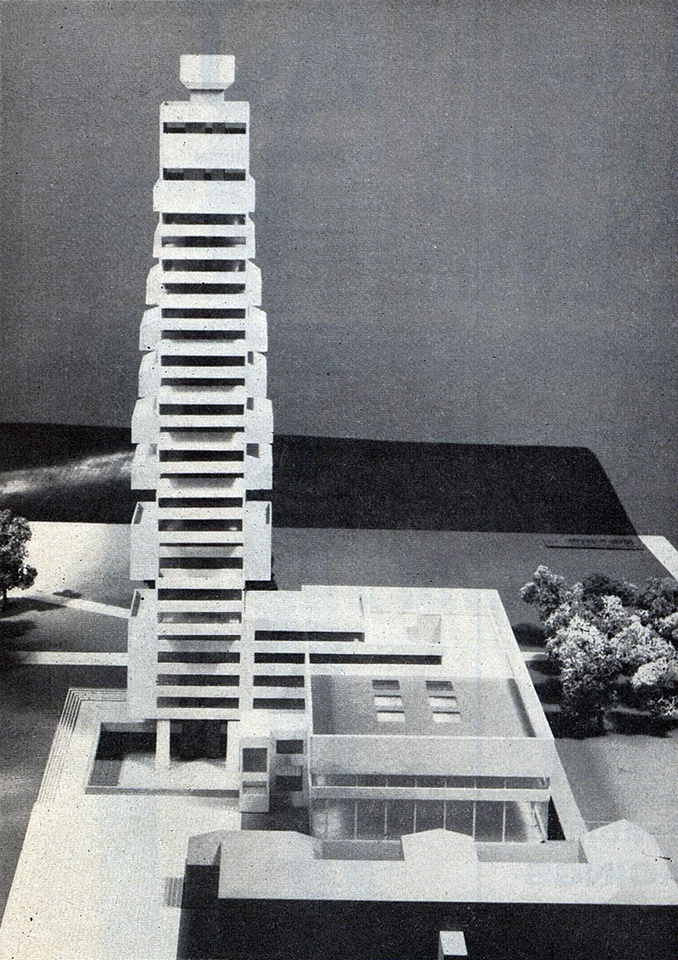

Designed by Sir Leslie Martin, the Tinbergen Building was the largest teaching and research building in the University, accommodating almost 800 people and providing a base for undergraduate studies in Experimental Psychology, Zoology, Biological Sciences and Biochemistry. Prior to Martin’s appointment, a scheme that included a 260ft tower of ‘fluid outline’, designed by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, was considered by the university’s Congregation. [1] Their tall solution was a reaction to the scale of accommodation required and an attempt to avoid ‘massive bulk’ of ‘something like a battleship lying across our path’.[2] Leslie Martins’ scheme, despite its stepped profiles, failed to evade such charges and it hulking form did little to fend off criticism. Building in historic Oxford seems fraught with obstacles and if ever the phrasing of ‘all of the people, some of the time’ were more apt, I am yet to encounter it. That said, one of the constant criticisms made by those encountering commissions in post-war Oxford was that the lack of a cohesive masterplan to govern development often ensnared them in an architectural ambuscade. In this building, Martin sought to overcome subjective critique and to position the architecture as part of a larger urban system based on an expandable grid pattern related to available land and built form. Martin’s important essay, ‘The Grid as Generator’ (1972), captured his research into form and plots sizes and in the Tinbergen Building it is possible to see some of the ideas in the essay applied to design and construction. [3] The basic idea was fitting for a city like Oxford wishing to preserve its dreaming spires – with identical conditions and larger sites, a spreading court form will place the same amount of floor space in the same site area in one-third of the height required for an island form. Thus, the Tinbergen Building assumed the form of a number of courts arranged along a spine and with the various wings stepped in profile to allow daylighting and roof terraces to the research laboratories. The spine was both for circulation and to house the irregular spaces of libraries and lecture theatres. The teaching and research rooms were planned to a standardised square 35ft module with a 5ft service space between them. The buildings southerly aspect was quite open and in its form and light tone had some similarities to Lasdun’s work at UEA. The concrete of the façade did not age well and developed quite a dreary appearance which did not help when the building was threatened with demolition. The discovery of a significant of asbestos was the final nail in the coffin in a sector where shiny new buildings by signature architects are common currency. The Tinbergen Building was a building for science planned with some robust scientific principles and undoubtedly an applied version of the architectural research that Martin so valued and assuredly defined in his development of the architecture department at Cambridge. The detailed design of the external envelope was as straightforward as the rigorous ordering of the internal spaces and without the mannerist over articulation of structure seen at St John’s College (Arup, 1976) and other post-war university schemes in Oxford. It was the appearance of the building, not the thinking behind it, that most likely saw it condemned – it was demolished in 2020 following protest that never gained any traction, a petition to save it garnered 25 signatories.

[1] Architect’s Journal, 20 June 1962, p.1362.

[2] Architects’ Journal, 27 June 1962, p.1448.

[3] Martin, L. (1972) ‘The Grid as Generator’, in Martin, L. & March, L. Urban Space and Structures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)