St. Augustine's Church

1968

St. Augustine’s is the Catholic Church for the parish and also the Chaplaincy for the Manchester Metropolitan University. It is within the All Saints campus that the robust and squat church sits calmly and with a degree of anonymity - afforded by its simplicity of mass and form and the predominant dark brown brick that seems to neutralise its presence.

The park around which the MMU campus is based, Grosvenor Square, was the site of All Saints Church and burial ground, and remains consecrated. Both All Saints and St. Augustine’s of nearby York Street were shelled during World War II, the latter in 1940. St. Augustine’s had a previous history of relocation and had moved from Granby Row in 1908, to York Street, whereupon it prospered as the major Catholic church of Chorlton-on-Medlock. The niche site located for the new St. Augustine’s, on Lower Ormond Street, faced east across Grosvenor Square towards Oxford Road and was flanked by the Ormond Building (Mangnall & Littlewood, 1881) and the Bellhouse Building, built in the Georgian style and attributed to the philanthropic Bellhouse family. All Saints was never rebuilt and subsequently the views west, across the park, are of this trio of buildings.

St. Augustine’s was part financed by the War Damage Commission and the budget was subsequently more generous than the usual Diocese of Salford commissions of the period. Desmond recalls the site and his desires and responses; he felt that the mass and form of his intervention were almost implied by the adjacent buildings and that he wanted to create a “sanctuary of repose, away from the busy street”. The entrance sequence is a very deliberate attempt to control this experience; climbing the shallow steps from the street, you are cupped by the tall masonry walls and then enveloped by the extended soffit of the narthex before crossing the threshold proper, through glazed doors, into said narthex. From the narthex the compressed view of the space about to open before you, through a second set of glazed doors, promotes a sense of anticipation. As one enters, the floor of the church slopes gently downward toward an open altar sanctuary to “allow as many people as possible to see”, but also contributes toward the sense that one is moving away from the street and focussing elsewhere. This focus is drawn powerfully, beyond the altar, to the massive and dramatic ceramic relief sculpture ‘Christ in Glory’ by Robert (Bob) Brumby.

Desmond commissioned Bob after seeing sketches of his. The brief was that the piece should not contrast against the dark brick interior if it were to be of such a scale; for fear that it would dominate the space. The artist was sent crushed brick samples to match his clay mixture to, and he submitted cartoons before constructing small mock -ups for the design team to inspect. Following one visit to Bob’s studio near York, Desmond was afraid that the piece would in fact be too overpowering. It was however, too late, and Desmond had to hold his nerve until the piece was revealed. The result is in fact quite spectacular, particularly in the morning light, cast from the east facing rooflights.

The internal atmosphere of the church is modified by the changes in light cast through the stained glass windows. The windows are of a colourful random and abstract design and ascend the full height of the walls between structural bays which themselves form enclosures to confessionals and stores. The pieces of coloured glass are suspended in concrete and were supplied by the now defunct Whitefriars company. The designer was a French artist, Pierre Fourmaintraux, who began working with Whitefriars in 1959, using the ‘dalle de verre’ (slab glass) technique that had been developed in France between the wars. His motif was a small monk variously painted upon, or cast into, the glass. In St. Augustine’s the motif is cast and highly stylised and can be found tucked away at the foot of each of the rear windows.

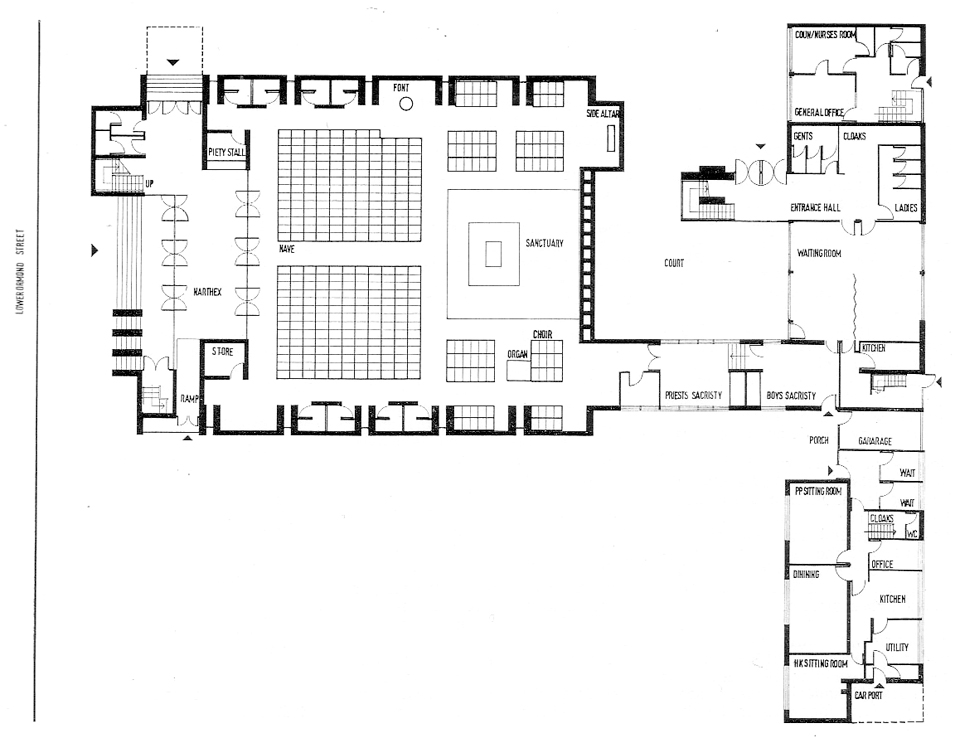

The stark formal expression of the building, suggest an architect concerned primarily with the contemporary as he practised; this is not however the case. When one considers the plan of the church, the orthodox elements are abundant; the side altar, the confessionals and the symmetry of the nave are all very mannered and conservative conventions. The church even sports a campanile rising from the Chaplaincy block to the rear. Desmond, a planner and forward thinker, now admits to reflection upon his love of cathedrals and monasteries and music. The breadth of his taste covers sacred polyphony, Baroque, late 19th & early 20th century French organ and English choral music. He also considers how subtly and subconsciously this affected and informed his ecclesiastical work.